KolmoLD

enable a new kind of computer networks, networks that are content-addressable, feature composable data, and let you distribute the code to read the data along with the data itself.

KolmoLD: Data Modeling for the Modern Internet

ABSTRACT

KolmoLD is a framework for content-addressable networking with a programmable layer: the data objects distributed across the network can contain program code to decode the data that is specified to be executed in a sandboxed environment and references other data objects based on a cryptographic hash function naming scheme.

Traditionally, the algorithms to access given data are delivered via a channel that is separate from the one used to deliver the data itself, and usually involves installing custom software that could introduce security risks. In contrast, KolmoLD enables the delivery of the algorithms and the data along the same channel and ensures security. The KolmoLD approach unlocks the promise of the information-centered networks: enabling true data deduplication, data reuse and optimal data delivery.

CCS CONCEPTS

- Networks → Future Internet; High-Precision Networking; Programmable Networks

KEYWORDS

Future Internet; Algorithmic Data Networks; Information Centered Networks; Content Addressable Networks ACM Reference Format: Dmitry Borzov, Tingqiu(Tim) Yuan, Mikhail Ignatovich, and Jian Li. 2019. KolmoLD: Data Modeling for the Modern Internet. In ACM SIGCOMM 2019 Workshop on Networking for Emerging Applications and Technologies (NEAT’19), August 19, 2019, Beijing, China. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 7 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3341558.3342198

INTRODUCTION

Whether the messages sent across a network contain images, text, or voice, from the perspective of the network layer within the OSI model, they are abstracted out to indistinguishable strings of bytes with a destination address. This design principle, the separation of concerns in the representation of data between the application layer and the lower abstraction levels, has been cited as one of the key principles that enabled the Internet’s success [11].

And yet, with time, the industry grew to learn the limitations inherent in this concept. It transpired that not all data is equal when it comes to networking. For example, it could be argued that VoIP traffic is more sensitive to high latency than, say, traffic for a routine software update, and thus should be given priority in processing, all other things being equal. The necessity to differentiate the categories of traffic was one of the major motivating factors behind the rise of the family of technologies referred to as software-defined networking (SDN) [9].

How can content distribution, one of the key traffic categories, be enhanced if the network was somehow cognizant of the meaning of the content shared? The concepts of algorithmic information theory, specifically the minimal description length (MDL) principle formulated by Rissanen, provides the theoretical basis for fundamentally more powerful network communication. According to this, optimal communication involves considering both the character of the message and the context the data recipient has [8].

While the practicality of applying such an approach to the problem of content delivery networking might sound far-fetched at first, there are, in fact, some well-known design patterns implemented in domain-specific content distribution systems that can be interpreted as its embodiment, even in a relatively basic way.

One example is software package distribution managers, such as the Advanced Package Tool (APT) system [1] for the Debian Linux family of operating systems. Such systems are responsible for downloading and installing software packages from a central package repository. It is common that a digital asset, such as a specific version of a software library, is used in multiple packages. Consider a scenario where the same library is used in two packages: package A and package B. If the user, who already has package A installed, wants to install package B, the APT client program code can recognize that a given library is already locally available, and thus only request and download the parts of the package it actually needs. In other words, leveraging the aspects of the meaning of the content at hand, in this case the inner structure of the software packages, leads to avoiding unnecessary traffic.

Another example is the encoding negotiation performed as part of the HTTP [6]. The browser announces to the server a list of the data compression formats that it supports with a special HTTP request header. This enables the server to select the correct encoding software for the content that the browser requested, with the certainty that the browser will be able to decode and render the content correctly.

This illustrates how being able to reference different data formats and incorporating the fact that the same message can be represented in different data formats leads to smarter communication.

Note how there is nothing specific to the domains at hand (the software packages or web content) in both examples presented. The optimizations described in the examples are general in nature and can be applied to any data shared across the network.

It is therefore reasonable to ask whether it is possible to design a general-purpose content delivery networking technology that introduces primitives to reflect some aspects of the meaning of the content being shared. In other words, whether content delivery can be empowered by being based on the MDL principle at the network level.

KolmoLD, the framework being presented in this paper, aims to be such a design.

CONCEPTUAL OVERVIEW

This section aims to provide a high-level conceptual overview of the KolmoLD framework as well as introduce core terminology. Note that more specific technical details can be found in the design section.

In our experience, the best way to introduce the core ideas behind our proposal is with the following primer analogy.

Pirate S obtains a treasure map and she needs help to find the treasure, but her pirate associates are dispersed across the Caribbean. She needs to send them the location of the treasure, so that they can meet her there.

One way to achieve that is to send out a copy of the treasure map to each pirate. However, pirate S realizes that it could be unnecessary in some cases. She is aware that some of her associates might have access to the map of the treasure island, albeit without the “X” marking the treasure spot. All they might require is a way to identify the map they need and directions to the treasure’s location. Others are more knowledgeable and can read navigational charts: these pirates just need the coordinates.

In other words, pirate S only needs to provide the pirates with enough information for them to reconstruct the treasure map on their side. But which pirate needs what? Enquiring what each pirate needs might incur a big overhead and is something pirate S does not want to do.

What pirate S does instead is produce a manifest for the treasure map and sends it to each of her associates:

The treasure map has the hash “A34F6”.

It can be constructed from these two formulas:

- those who have a map of an island with the hash “52347” can mark the spot fifty feet South of Spyeglass Hill and they shall have the map.

- those familiar with the navigational charts specified in the textbook with the hash “45006” will find the treasure at “23.8’N 82.23’W”

The formulas are ways to construct the manifest’s target data, in this case the treasure map. Each formula contains references to other data objects in the form of cryptographic hash function-based data object identifiers (or DOIs).

Upon receiving the manifest, pirate A realises that her sister has the map of the treasure island, asks her for it, and fills in the location of the treasure to construct her treasure map. Pirate B uses the textbook “45006” and marks the location of the treasure using the specified coordinates. She can be sure that she interprets the coordinates given correctly as she could verify the hash of her navigation reference.

Pirate S was able to optimize the distribution of the treasure map to pirates by distributing information about the properties of the content at hand, which other pirates were able to leverage to find the optimal way to reconstruct the data they were after.

As in the case of the treasure map, any content can be described with manifests within KolmoLD. Such descriptions involve DOIs to other data objects and reflect the content’s inner structure. The naming scheme based on the cryptohash function makes such references unambiguous and verifiable. The set of such manifests is free from the particulars of the underlying network such as, say, the node IDs, and is only based on the data it describes. In that sense, KolmoLD’s manifest syntax can be seen as a data modeling language.

The reference to the navigation textbook is a special type of data object introduced in this methodology that is interpreted as an algorithm to be applied to the referenced data as part of the manifest description. These special data objects are referred to as kolmoblocks. Such algorithms can specify the decoder for the data compression format used, for example.

Altogether, network agents could potentially read and comprehend the data model specified with KolmoLD and make smarter decisions on how to reconstruct the content they are seeking, achieving a conceptually more powerful content delivery network.

BACKGROUND

This section offers an overview of the key academic results, as well as products and projects relevant to the discussion.

The MDL principle

The concepts of Shannon entropy and Kolmogorov complexity are often quoted as the bases for two major approaches to information theory.

As the approach based on Shannon entropy offers stronger framework for quantitative analysis, it tends to see wider adoption. However, the assumptions that come with the concept of Shannon entropy tend to break apart when they are applied to complex challenges in networking. Specifically, the concepts of the abstract source and constant probabilistic distributions do not fit well with the challenges of engineering practical content delivery networking.

Some recent developments in networking theory illustrate this. A new field of network encoding has emerged in recent years , where the shape of the network is taken into account in message encoding to achieve more efficient communication. The theory attracted considerable interest and contributed to aspects of the 5G family of technologies. Yet this domain cannot be described within the Shannon entropy-based methodology.

We propose using algorithmic information theory (based on the concept of Kolmogorov complexity) instead, and specifically, the minimum description length (MDL) principle formulated by Rissanen as the theoretical foundation to discuss and formulate our approach 8.

Let us give a minimal overview of how it applies to our case.

We start with a network node seeking to retrieve our target data object \( D \). We are given a set of models \( M \) that can be used to characterize \( D \). The following cost functions are specified:

(1) \( t \): traffic, the amount of data to be retrieved from the network,

(2) \( c \): computational cost,

(3) \( m \): computational memory requirements cost.

A given \( M_i \) model from the set \( M \) can be applied to describe (that is, encode) \( D \), with the efficiency described with a cost vector:

\begin{equation} \vec{C}(M_i, D) = \bigl( t \left\{ M_i(D) \right\} , c \left\{ M_i(D) \right\} , m \left\{ M_i(D) \right\} \bigl) \qquad (1) \end{equation}

However, this is not the full cost of applying \( M_i \). The node also needs to be able to recognize the model applied and use it to decode the target \( D \). If the node already has the \( M_i \) decoder, maybe as a locally cached kolmoblock, it only needs a reference to that kolmoblock. Otherwise, the node has to first retrieve the full description of the decoder first, in the form of downloading the kolmoblock. This cost of the \( M_i \) description does not depend on the target \( D \) and can be represented as follows:

\begin{equation} \vec{R}(M_i) = \bigl( t \left\{ M_i \right\}, c \left\{ M_i \right\}, m \left\{ M_i \right\} \bigl) \qquad (2) \end{equation}

Given both cost vectors for each \( M_i \) in \( M \), the network node can find the optimal model for obtaining the data object.

The total cost for the network node is:

\begin{equation} \min_{ \forall i \in M } U\left\{ \vec{C}(M_i, D) + \vec{R}(M_i) \right\} \qquad (3) \end{equation}

Here \( U \) is the utility function for the given network node that reflects the trade offs between different types of costs specific to this given node.

The models represented above could be any method used to describe data, for example a data compression algorithm, such as the LZ-76 compression [12]. Models could also reproduce a specific data object by leveraging other data objects on the network. For example, the data object that represents the string ‘hello world’ can be described by a model that appends the data object “world” to the data object “hello”.

In other words, \( \vec{R(M_i)} \) is the cost of retrieving the data objects needed to construct the \( M_i \) model:

\begin{equation} \vec{R(M_i)} = \min_{ \forall j \in M } U\left\{ \vec{C}(M_j, M_i) + \vec{R}(M_j) \right\} \qquad (4) \end{equation}

The MDL principle suggests that the key to optimal communication is the ability to calculate the cost vectors for the set \( M \) and target \( D \) for each given network node. The KolmoLD design offers network primitives that allow for sharing the information necessary to calculate the cost vectors.

Information-Centric Networks

The network protocols [2] that form the backbone of the Internet are based on the telephony network model: they enable point-to-point communication between two nodes by specifying the format for messages to be relayed from one node to another. As the Internet matured, the point-to-point network communication pattern gave way to the dominance of other ones such as, notably, content delivery, where one provider is tasked to deliver the same content to multiple consumers.

While the telephony network model has proven to be resilient and powerful in numerous contexts, its advantages are more limited when used for pure content distribution. These complications can be compared to those that will arise when trying to broadcast television or radio content over the telephone network.

An alternative network communication paradigm, called the information-centric network (ICN), has been proposed as a viable alternative for content distribution [14]. On a point-to-point network, a node that wants to obtain a specific data object must send a request to another node that is known to have that data object. In contrast, on an ICN the requests are not defined by the addressee, but by the content (more specifically, the data object) they are looking for. Such content requests can then be served by any node that has the content.

One way to illustrate the advantages of the ICN model is to consider the problem of caching JavaScript libraries. While each web application’s JavaScript code is ultimately unique, it usually includes JavaScript libraries that are built to contain elements and functionality that commonly needed within web applications. As a result, multiple websites might include the same version of a library and such libraries commonly comprise a sizeable portion of the overall JavaScript code. According to one analysis [3], this practice is so common that it is estimated that up to 72% of the websites use at least one of these JavaScript libraries. Even more strikingly, 79% of those websites use the most common JavaScript library, jQuery.

As a best practice, the web developers prefer hosting all the JavaScript code and libraries they require on their own, rather than referencing the shared URLs, to minimize security issues and avoid dependencies on third parties for their end-user experience. As the end-user navigates from one website to the next then, the browser is forced to download the same copy of the JavaScript library anew.

ICN’s architecture is designed to gracefully handle situations such as these. Under ICN, a given JavaScript library can be referenced not by a URL, but by a content identifier. The copy can then be obtained from the closest node willing to serve it, and cached and re-used on local devices.

ICN received considerable academic interest, resulting in multiple proposals and implementations. Named Data Networking (NDN) [13] is an example of a high-profile project [2].

What’s in a name?

An ICN architecture proposal must specify numerous aspects of the problem: routing, data discovery, scaling [14]. One design decision is at the core of all these aspects and can be used as the basis for the classification of ICN proposals: the naming scheme. This is specifically how the data objects in the network are referenced and identified.

Using cryptohash functions as the basis for the naming scheme is one of the options. Cryptohash naming is a well-known design pattern also referred to as the content-addressable storage pattern. Some well-known software projects that can be viewed as ICN proposals, IPFS [4] and BitTorrent [5], adopt a hash-based naming scheme.

On the one hand, this approach provides the following advantages:

(1) Universal naming convention: the hash-based name is unambiguous, global, and self-contained; it does not depend on the context within which it is used;

(2) Does not depend on the circumstances of origination: The only thing that defines the hash-based name is the data itself; not the circumstances behind who, when and with what purpose produced or published the given data object;

(3) Self-certifying name: It is easy for the data receiver to verify whether the data object matches the name;

On the other hand, the drawbacks of this approach are as follows:

(1) Off-by-one errors: while data reuse is often quoted as an advantage of the approach discussed, its impact has been deemed relatively limited, according to some quantitative analysis research. The reason is fundamental: two data objects that are only different by a bit will be identified as two different data objects with two distinct hashes. There is no way for the network to recognize and leverage the case where two objects contain related information in any way;

(2) No metadata: the data by itself is virtually useless without the information concerning the data type or data format that is used.

We have illustrated that KolmoLD also adopts the hash-based naming scheme. Yet, the other contribution KolmoLD makes is providing the ability to encode arbitrary algorithms that are pertinent to the data object at hand. This means that similar data objects can be linked together with formulas describing ways to construct one data object from a related one, meaning that the decoder for the given file format can be described in an algorithm data object and referenced within the manifest.

Thus, KolmoLD’s approach brings about the advantages of hash-basing naming while mediating its drawbacks.

The right codec

As data compression format (or codec) choice mechanics is the key for efficient content delivery networking we argue that it should be incorporated as a component of network design.

Choosing the optimal codec goes beyond achieving just the highest compression ratio [12]: application context and end-device capabilities also need to be considered. For example, low-power devices with limited processing power would struggle to run computationally expensive decoders. Some other codec features that might influence the ultimate choice are domain specific, such as progressive download functionality that could display a lower resolution of an image to the end-user once a part of the whole data object has been downloaded. A higher resolution of the image will then be shown as the rest of the data is received.

In general, the more assumptions that can be made about the data, the better codec can be designed. The new generation of compression algorithms provide tooling to leverage this. For example, zstandard allows you to “train” your codec by feeding it the samples of data you would like to compress and building up a special data structure, a dictionary, of frequently encountered tokens.

Another example of the power of highly-specialized codecs can be illustrated with online multiplayer video games. The game architecture consists of a game server that keeps track of the state of the shared virtual environment. The information it needs to keep track of is specific to this online video game: player navigational inputs and player inventory, for example. The game server will send this information to all participating player client applications. Both the client and the server’s program code is highly tuned and optimized to only send the absolute minimum of the data required. The client application then uses it to render the video stream that constitutes the game environment. Thus, the video game program code can be thought of us a special type of video codec: the one that only works for the video stream of that given video game. The more narrow the type of data we target, the more efficient compression we might achieve.

Based on that, it would seem reasonable to expect a plethora of narrow-use domain specific data compression formats and codecs available in the marketplace. For example, video codecs that are tailored for specific domains, such as videos with solely e-learning content.

Instead, software engineers are usually stuck with several decades-old general-purpose data compression formats: an LZ-based compressor for structured data such as text and bytecode; jpeg or png for images; and so on.

The reason is directly related to the effort required to see adoption of new codecs in the industry. Not only does the developer of a new codec have to design and implement one, she also needs the end-user agent to be able to recognize and use it. That usually means that new software supporting the new codec must be deployed on the end-user system before an application can use it.

KolmoLD takes an approach that sidesteps this challenge altogether: what if you could distribute the decoder algorithm along with the data itself? This would enable the content publisher to select the codec that works best for the given data type without worrying about the codec’s support. The recipient would be able to download the decoding algorithm just like any other content and use it to decode the given data.

In this scenario, running the decoder algorithm effectively amounts to executing untrusted program code, which raises security and performance concerns. The execution environment needs to be sandboxed from the host machine with all the security issues carefully considered and addressed.

Fortunately, there are developer communities who have gained experience addressing these challenges. The Ethereum Virtual Machine is an example of deterministic execution of Turing-complete programs that includes references to other code based on the hash naming scheme. Browser-based encapsulated execution of JavaScript code is another example.

KolmoLD proposes a specification for such a sandboxed environment where Turing-complete algorithms can be executed in a runtime environment that is only able to access other input data objects, and outputs the target data object.

The practical implementation for it is built on top of WebAssembly [7]. This allows us to tap into the research and expertise accumulated in that community to solve a similar problem.

DESIGN

At its core, KolmoLD provides primitives to describe the relations between the data objects shared and distributed across the network. The solution consists of the following components:

(1) KolmoLD manifest syntax that allows network nodes to describe the data objects they handle, and their relations with other data objects.

(2) WebAssembly-based kolmoblock format [7] to encode arbitrary programs that can be executed to retrieve data objects.

(3) A versioned registry of approved and supported WebAssembly-based modules that contain codecs and algorithms.

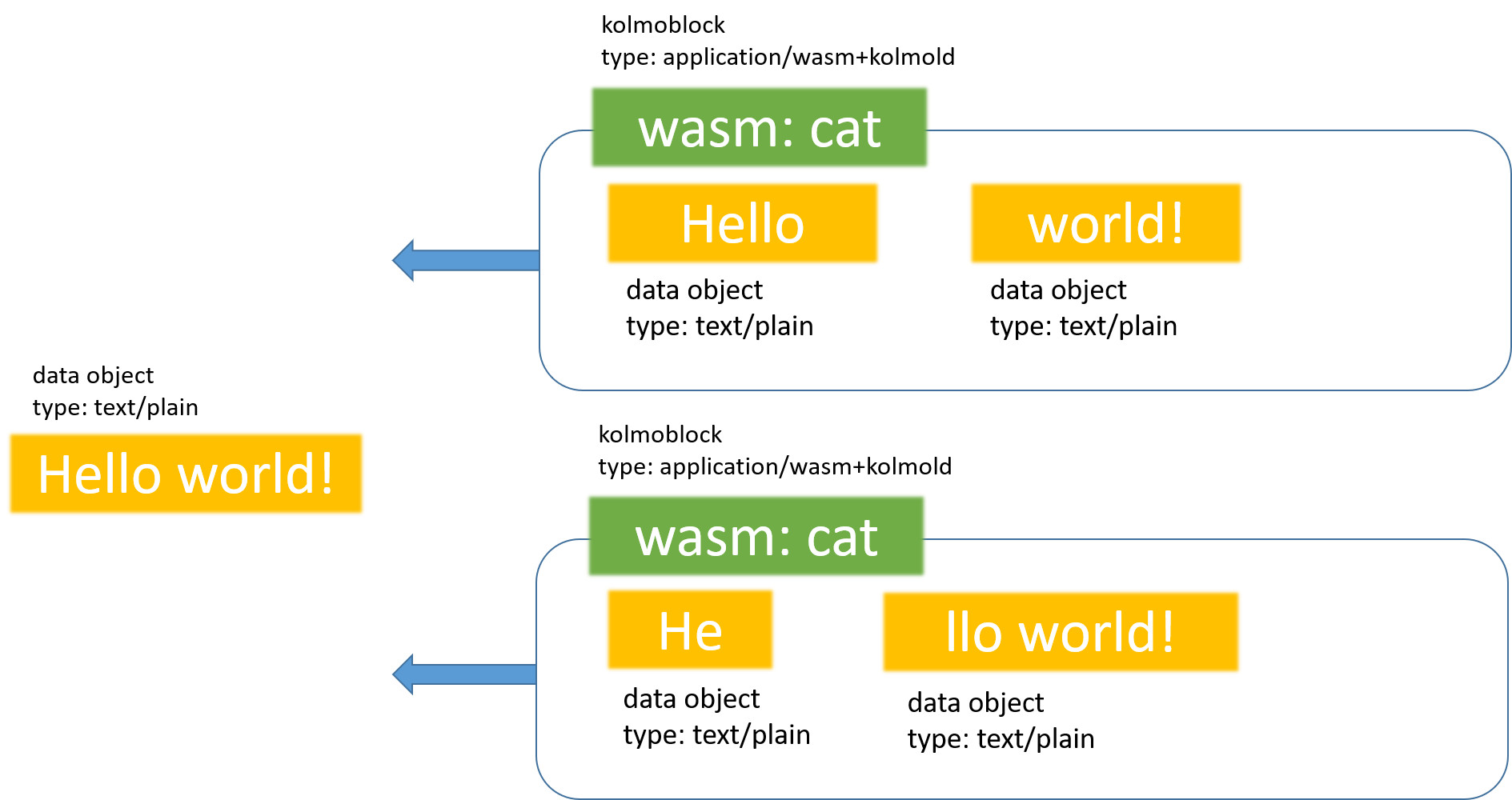

Consider the data objects in the following “Hello World” example:

The “Hello world!” string can be constructed in two ways: by concatenating strings “Hello ” and “world!”, or by concatenating strings “He” and “llo world!”.

This basic data model consists of the following data objects:

(1) kolmoblock “cat”, which encodes the logic to concatenate input strings;

(2) strings “Hello world!”, “He”, “llo world!”, “world!” and “Hello”.

This model can be described with the following manifest for the target string “>Hello world!” with the hash “B5D40” (we will be using only the first 5 digits of the hex representation of SHA-256 in our examples):

(match,

(doi, "B5D40"),

(exec

(doi, "cat",

type: "application/wasm+kolmold"

),

(doi,

type: "text/plain",

data: "Hello ",

)

(doi,

type: "text/plain",

data: "world!",

),

)

(exec

(doi, "cat",

type: "application/wasm+kolmold"

),

(doi,

type: "text/plain",

data: "He",

)

(doi,

type: "text/plain",

data: "llo world!",

),

)

)

The data object is a key abstraction of the KolmoLD methodology. It refers to any identifiable chunk of data of arbitrary (up to a multiple of bytes) size. The KolmoLD manifests allow for describing the properties of the data object, called a kolmoblock, and the relation between kolmoblocks.

The manifest syntax supports three types of expressions: doi, exec and match. All were used in the example above.

Or, more formally, in the Extended Backus-Naur form (EBNF):

kolmold_expr ::= { doi_expr | exec_expr | match_expr }

We will now review each in more detail.

DOI expression

Data objects are identified by the data object identifier, or the Data Object Identifier(DOI). The doi expression allows for referencing a specific data object.

The doi expression syntax is defined as follows:

doi_expr ::== doi [<ASCII-string>]

[ type: <ASCII-string> ]

[ size: <varint>]

[ data: <hex-literal>]

[ publisher: <hex-literal>]

[ sign: <hex-literal>]

[ func-verify: kolmoblock_expr ]

[ func-sign: kolmoblock_expr ]

The first argument is the cryptohash-based ID. Next follow optional attributes that provide additional metadata about the data object being described:

type: MIME type-based data object type,

size: size of the data object in bytes,

data: Data literal of the data object,

publisher: public key used for digital signature.

sign: the digital signature.

func-verify: Verifier function used, expects a registered kolmoblock doi,

func-sign: Digital signature verifier, expects a registered kolmoblock doi.

The data literal attribute is a special one: if the data object contains only the data itself as part of the doi expression, many other attributes such as size or the hash ID are redundant.

In the “Hello World” example there are two different MIME types defined. The concatenation function kolmoblock cat has the MIME type application/wasm+kolmold. This indicates that the cat kolmoblock contains program code written in the WebAssembly bytecode format. The dependency blocks that contain the strings that will be concatenated, are defined as type text/plain.

Exec expression

The keyword exec is used for a formula expression. That is, to specify a data object that is an output of a kolmoblock code sandbox execution. The cat kolmoblock is an example of this and illustrates how a data object in the KolmoLD framework can be described as an output of an algorithm encoded in a WebAssembly-based format.

The MIME type for the kolmoblock format is application/wasm+kolmold, which indicates that our implementation is based on the WebAssembly (wasm) module format. The standard is a subset of pure WebAssembly format, with non-deterministic operations taken out.

In addition, the kolmoblock format provides the following format specifications:

(1) Entry point function: wasm module’s exported function main is used as an entry point for running the kolmoblock bytecode. The main function is expected to be of the type -> i32.

(2) Determinism: KolmoLD expressions are deterministic and reproducible, however WebAssembly’s 1.0 version is not fully deterministic. In order to address this disparity, KolmoLD outlines the unspecified behaviour of non-determinism.

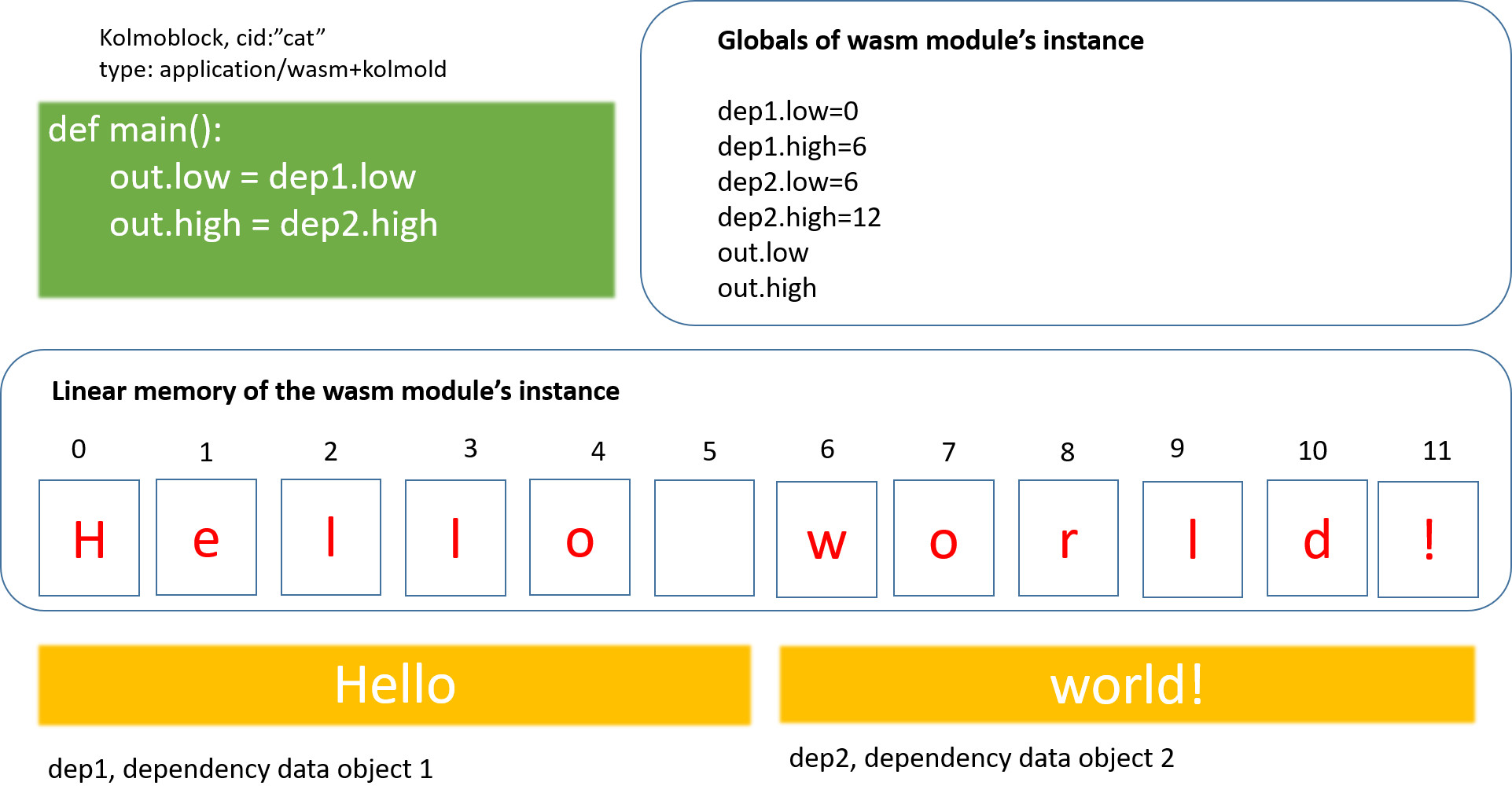

(3) Input data object loaders: exec expressions allow for denoting other data objects as input (or dependency) data objects for the execution at hand. The kolmoblock runtime is responsible for preloading the input data objects into the WebAssembly module’s linear memory before the module’s code execution and informing the WebAssembly code of the boundaries of the input data object’s data in linear memory.

The kolmoblock WebAssembly module’s linear memory with the dependency blocks preloaded can be illustrated as:

Figure 1: The dependency data objects are preloaded into kolmoblock’s linear memory

Figure 1: The dependency data objects are preloaded into kolmoblock’s linear memory

The dependency data objects are identified by their index number, starting with 0. The exec expression syntax is as follows:

exec_expr ::= "exec" <wasm-module-cid> op_cap_expr* mem_size_expr*

[ op_cap: varint ]

[ mem_size: varint ]

[dep-exprs]

dep-exprs ::= doi_expr [dep-exprs]

wasm-module-cid: The cid of the executable kolmoblock wasm-module,

op-cap: Operational limit specified in webassembly instructions evaluated,

mem-size: webassembly memory limit specified in the number of 64kB pages,

dep-exprs: Ordered list of dependency data objects.

Match expression

A key feature of KolmoLD is the ability to express the same content as generated in multiple ways. The match expressions are used to state that multiple descriptions of data objects, whether exec or doi expression-based, are producing the same data object.

Match expressions are similar to pattern matching expressions in functional programming languages such as Haskell.

The match expression syntax is as follows:

match_expr ::= match <expr> <exprs>

expr ::= doi_expr | exec_expr

exprs ::= <expr> <exprs>

Let’s say, we have the same data object being referenced with two different dois obtained with different hash functions: ‘five spaces’ for the hash_func1 function, and ‘ffee45’ for the hash_func2. This can be stated with the following expression:

(match,

(doi, 'five spaces', func-verify: hash_func1),

(doi, 'ffee45', func-verify: hash_func2)

)

Let’s say we need to express that the data object with doi ‘1’ can be obtained by executing a kolmoblock with doi ‘fibonacci’.

This can be done with the following match expression:

(match,

cid('1'),

( exec

cid('fibonacci')

)

)

With the basic building blocks of match, doi and exec expressions, the manifest syntax provides primitives to describe the information about the underlying structure of the data shared across the network.

CONCLUSION

KolmoLD offers new primitives for low-level content distribution networking. Network nodes can leverage them to share and distribute information about the character and underlying structure behind the data objects that make up the content shared.

This enables network nodes to make better decisions on how the content should be retrieved that take into account the context of each given network node, leading to the MDL-based network communication.